THE CONTEXT

All around us, people are inadvertently saying and doing things that are potentially problematic or hurtful with regard to race.

THE PUZZLE

Despite how frequently this happens, we are not great at productively speaking up. How can we do it better when the topics are so complex? How can we do it in a way that builds relationships and deeper understanding?

Noah is obsessed with those huge stuffed animal toys that you can win in carnival games. He is nine years old and white. I am friends with his parents who told me I could write about his latest carnival experience. Noah is not his real name, and I’ll keep out identifying details.

Every year, Noah goes to the Great Frederick Fair in Frederick, MD. The Great Frederick Fair is pretty incredible. You can watch cows being born, check out contests for the best goat, eat all the good fair food classics, and spin and twist on rides late into night. It’s been going on for 157 years. It’s such a big deal around here that children get a day off from school to go. I couldn’t possibly describe the Fair in all its glory. If you’re in the mood to read a good fair description though, I recommend this one from David Foster Wallace.

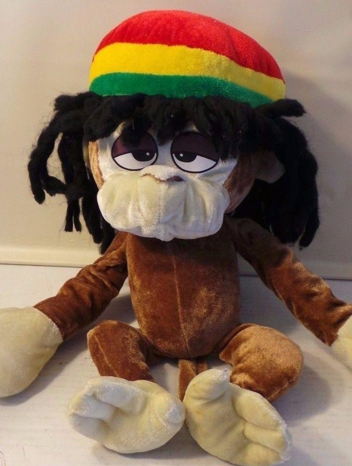

Back to Noah. At the Fair, he longingly eyes those carnival games where you toss a softball into a bucket or try to hook a ring on a bottle. But his parents, like most parents I know, do not like throwing their money away, so Noah doesn’t often get this chance. Until this year, that is, when his grandmother came to town. She took him to the Fair and his dreams came true. He managed to win the grand prize and choose whichever large stuffed animal toy he wanted. He carried his prize around with him all day at the Fair. He carried it around with him all afternoon in the house. He could not have been happier. This is what his parents saw him carrying around when they got home from work:

What's your reaction to this picture? You might feel sick about it. You might feel angry about it. You might not feel much. I bet most people who consider themselves sensitive to race issues have a reflex reaction that this is bad. Really bad. But I’m also willing to bet that a lot of those same people, especially the white ones, would struggle to explain to a nine-year-old (or an adult for that matter) what exactly the problem is with this carnival monkey with dreadlocks and a Jamaican hat. Noah’s parents did not hesitate. They started some conversations right away, and as painful as it was, together they got rid of that monkey.

What would you say if you were in their position? How would you say it? If it had been an adult who chose that monkey, many of us might just shake our heads or say, “that’s messed up” or “that’s really racist” and “how could you not know this?” But we don’t do that with children. Let's use our sensitivity with children to think about how we might approach these conversations when an adult "messes up."

How We Can Do Better

[1] Assume good intent. For the most part, people are moving through their days trying to be good people. Noah obviously wasn’t trying to do anything bad by choosing that toy. And even though the representation was harmful, his parents assumed good intent. They might have said things like, “Of course you didn’t know this.” Or “Of course you didn’t mean any harm.” Assuming good intent allows Noah, or anyone else we might talk to, to hear what is being said – to hear the impact of their words or their actions without feeling the need to first defend their intent. Caveat: sometimes people don’t have good intentions. In that case, throw away this guideline along with the Rasta Monkey.

[2] Explore together. Adults have two unproductive impulses when they notice something that might be offensive or problematic. One is to just not say anything. Speaking up is difficult; it doesn’t usually go well; we don’t exactly know what to say; we’re going to then have to deal with the tension we create. So we let the moment pass and then it’s too late. Or we call people out, in an oppositional way. Neither of these options would have worked for Noah’s parents. They HAD to say something and they had to do it while prioritizing their relationship with Noah. It's a good strategy. What if we could do this with adults too? Instead of ignoring the problem or aggressively criticizing in an oppositional way, we could make sure to say something and then explore together why it might have felt bad or why it might be problematic. This allows us to maintain the relationship with our friends, family, co-workers or fellow citizens, while at the same time allowing us to not feel like we have to know all the answers. We could even try this approach online. It’s not easy. It sometimes feels better to fire off a particularly clever or funny call-out. And sometimes that may be exactly what is needed. But if our goal is really to make positive change in the world, the thing that feels best to say might not be the most effective.

[3] Seek deep understanding. What if Noah’s parents had just taken away the monkey, told him it was offensive, and left it at that? He would likely be left feeling ashamed, powerless, and resentful. That's not very productive. But we're often left at this point speaking with children or adults when we don't know what to say or we don't have all the information. "Exploring together" might need additional resources. Though I know much of the answer on this question, I wanted to see what would happen if I just googled, “What is the problem comparing Black people with monkeys?” I got some pretty helpful resources in a split second. When we admit that we don't have all the answers, we illuminate the complexity of these issues and we model curiosity and humility. By building deeper understanding together with Noah, he can feel invested in the project of growing as a person and can feel empowered to speak up for positive change when something doesn’t feel right.

What we might actually say to build deep understanding with a nine-year-old (or 49-year old):

[4] Acknowledge the history. There is painful history in how this country was formed, and the Rasta Monkey points to some of the worst of it. The United States founders had some great ideals, including that all people should be treated equally. But at that point, people most horrifically weren't treated equally. Africans and African Americans were enslaved by white landowners. People didn’t know how to square the ideal with that reality. Thinkers at the time argued that Africans weren't even fully human. Scientists, seeking confirmation, measured people’s skulls and told the world that they had proved that all humans could be divided into groups of people called races. They made fancy charts to show that some races were of higher intelligence than others. They even compared African races to monkeys and apes to make a claim for lower intelligence. THIS IS TOTALLY NOT TRUE and the deceitful methods of those earlier scientists have been exposed. Even though we know better now, those messed up ideas still linger. When people see this monkey, which has hair and a hat that make him seem like a Black person from Jamaica, it links to both that tragic and painful history and the present reality in which African Americans are still not valued equally today.

[5] Break the cycle. The Rasta Monkey is a problem because it keeps harmful and wrong ideas in the world. Children have these incredible developing brains that seek out information and construct knowledge, even when they are not paying attention. All of our brains do that, learning subconsciously from what we see and hear, but it's especially critical to think about this process with children as the foundation of their brain architecture gets built. If they see distorted representations of groups of people, their brains might learn those wrong ideas – that some groups of people are more intelligent than others, that some groups have higher potential, that some are dangerous. This dopey looking Rasta Monkey by itself obviously doesn't teach a developing brain everything. But it's not just the Rasta Monkey. Those subtle messages about how some groups are valued more than others surround us - on tv, on news, in jokes, in books, etc. Because they are so present in our culture, even if adults explicitly teach children that "everyone is equal," young brains have already figured out that people are not valued equally. And it's those unconscious biases that impact so much - who gets challenged in school, who gets suspended from school, who gets hired, who gets trusted with the big projects, who gets promoted, who gets stopped on the street, etc. If we don’t do something to stop those ideas from getting passed on, those same ideas will just keep getting perpetuated across generations. And don't believe the hype that the younger generation has it all figured out. Research shows they have many of the same unconscious biases as older generations. That's why it's so important to speak to children about Rasta Monkey and everything else we see that might be a problem. We have to break that cycle.

[6] Start early. Children aren't too young for talk like this. Many of you know this all too well, having had painful conversations with children about their identities and how the world will see them and treat them. I also know that others of you, especially white parents, prefer to avoid the sadness and heaviness of these issues with your children. However, it's really important. Nine is not too young. I'd start thinking about this with three- and four-year-olds! Their brains are picking up on the subtle cultural cues whether we like it or not. But for some parents, it feels forced. Recognizing that, I developed an iPhone app many years ago to facilitate conversations with young children about race. It's free, check it out!

Here are some things that you might convey in those early conversations: (a) there is a lot to learn about our social world; (b) there is work to be done to create a society where people are truly valued equally; (c) it's important to speak up. Say, "I don't agree with that joke" or "That feels wrong to me;" (d) it's ok if you don't have all the answers; and (e) come to me if you have questions on these serious topics and we can figure it out together.

[7] Take responsibility. All of us must work to make things better (more equal and more inclusive). Even a nine-year-old has power to make their friend groups, their classroom, their school, and their neighborhood more positive and more inclusive. Certainly adults have that power and that responsibility at work and in the world. It's not enough to just do no harm. We all have to actively create the society we want. Having these conversations is a critical piece of that, and that responsibility should start falling more on those people who are not directly impacted. White people and men, for example, need to speak up as allies to create this more inclusive world. Anyone want to start by getting these fairs to stop giving away this monkey?

We can do better by speaking up about race.

Photo by Nick Fewings on Unsplash